The Impact of the Williams Syndrome Mutations on Neural James S. McDonnell Foundation Collaborative Activity Award: |

Program Directors:

Ursula Bellugi, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

David G. Amaral, University of California, Davis

Co-Investigators:

Julie R. Korenberg, University of California, Los Angeles

Edward Callaway, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

Marcus Raichle, Washington University School of Medicine

Steven Suomi, NICHD, Bethesda, MD (consultant)

Contact Information:

| Ursula Bellugi Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience The Salk Institute 10010 N. Torrey Pines Rd. La Jolla, CA 92037 Tel. (858) 453-4100 X 1222 Fax (858) 452-7052 bellugi@salk.edu |

David G. Amaral Center for Neuroscience University of California, Davis 1544 Newton Ct. Davis, CA 95616 Tel. (530) 757-8813 Fax. (530) 754-7016 dgamaral@ucdavis.edu |

INTRODUCTION

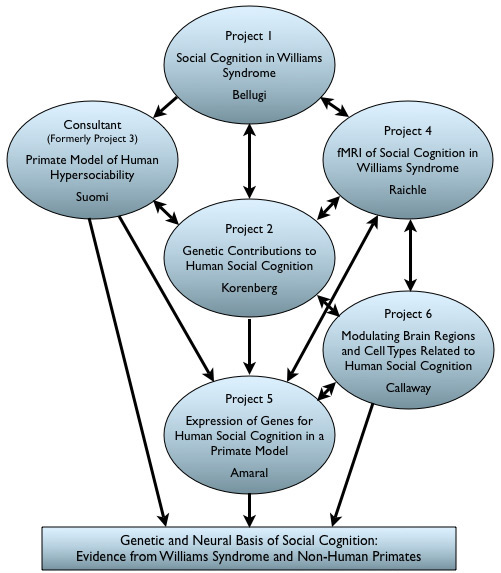

How can a life-altering neurodevelopmental disorder such as Williams syndrome help to unravel the mysteries of the brain? How can an understanding of the genes responsible for the alterations of social behavior in Williams syndrome lead to the discovery of neural systems that underlie social cognition? How can the power of molecular biology and functional magnetic resonance imaging be used to refine knowledge of the neural substrate of social cognition? And how soon will we be able to create a primate model of Williams syndrome in which to study the neurobiology of social function?

During the last three years, the neuroscientists listed above have formed the core of a James S. McDonnell Foundation funded series of meetings entitled, “Panel on The Cognitive, Neural and Genetic Bases of Social Behavior.” The panel meetings were held twice each year at The Salk Institute and were designed to promote discussion and planning of how to forge links between genes and cognition. Panel meetings included presentations on such issues as: 1) The neural systems underlying social behavior; 2) New genetic approaches to the study of social behavior; 3) Animal models of genetic disorders; 4) Techniques for transgenic manipulation of rodents and primates; 5) The role of the frontal lobes in social behavior; 6) Three contrasting genetic disorders - Williams syndrome, autism, fragile X - and their contrasting social behaviors; 7) Models for linking genetics, behavior and neural systems.

The meetings, which involved small groups of top scientists across several relevant disciplines, culminated in a three-day retreat held in 2001. Building on our exciting discussions over a two-year period, we are now prepared to propose an integrated genetic, neural and behavioral approach to the questions raised above that can provide powerful insights into the biology of social behavior. Moreover, this program could potentially produce, for the first time, a comprehensive view of the critical brain regions involved, and clues to the genetic pathways underlying, affiliative social behavior.

Through our planning meetings, it has become increasingly clear that attempting to explore pathways from genes to cognition mandates the development of a new field of research that has novel, technical and theoretical challenges. We are now in a position to exploit knowledge gained from a human genetic disorder, such as Williams syndrome, to develop animal models in which biological mechanisms can be more effectively studied. While much territory remains to be charted, we believe that we can begin the exciting and new process of using molecular and genetic technologies to produce primate models that demonstrate social behaviors, and alterations of normal social behavior, that are remarkably like those of humans.

In this application, we propose to use information gained from a genetic, behavioral and neuroimaging analysis of human subjects with Williams syndrome coupled with neuroanatomical, molecular lesioning and behavioral studies in nonhuman primates to define systems in the primate brain that are intimately involved in the mediation of component processes of social cognition. Given that the long-term well-being of societies is increasingly determined by the social behavior of individuals, this research program will have far reaching implications. Increased understanding of the biology of social cognition will impact fields ranging from psychiatry, to criminology to philosophy and religion. While the area that we have chosen to investigate is far reaching, the collaborative activities that are proposed are highly focussed on themes that can illuminate the cognitive, neural and genetic basis of social behavior.

WHY WILLIAMS SYNDROME?

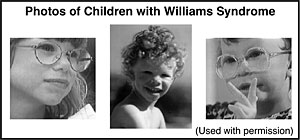

The overarching premise of this program is that the genetically based Williams syndrome may provide a unique window on how decreased expression of a small set of specific genes can lead to hypersocial and excessively affiliative behavior. Williams syndrome is a rare (1:20,000), genetically based disorder that results in a distinctive facial morphology (see Figure) and cardiovascular stenosis. It also typically results in a distinctive cognitive phenotype that has peaks and valleys of abilities both within and across domains: (a) relatively strong language in adolescence and adulthood; (b), specific deficits in spatial cognition, but strong face processing (Bellugi, et al, 1999, 2000).

The overarching premise of this program is that the genetically based Williams syndrome may provide a unique window on how decreased expression of a small set of specific genes can lead to hypersocial and excessively affiliative behavior. Williams syndrome is a rare (1:20,000), genetically based disorder that results in a distinctive facial morphology (see Figure) and cardiovascular stenosis. It also typically results in a distinctive cognitive phenotype that has peaks and valleys of abilities both within and across domains: (a) relatively strong language in adolescence and adulthood; (b), specific deficits in spatial cognition, but strong face processing (Bellugi, et al, 1999, 2000).

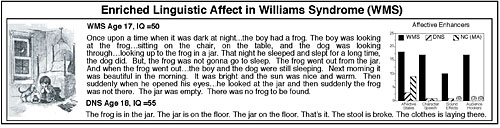

The focus of the current proposal stems from recent studies about the social nature of individuals with Williams. Individuals with Williams syndrome typically demonstrate an overly friendly, engaging personality that is characterized by an attraction to strangers and excessive sociability. Williams subjects demonstrate an unusually positive expression of affect (Jones, et al, 1998) and abnormally expressive language (Losh, et al, 2000). They exhibit an intense interest in faces (Figure at right) and strong proficiency in processing unfamiliar faces (Bellugi et al, 2000), as well as show unusually positive social behavior even from infancy; they have a striking capacity for empathy (Jones, et al, 2000; Reilly, et al, 1990 & in press; Losh, et al, 2000; Tager-Flusberg, et al, in press; Levine, et al, 2000). Thus, a prime characteristic of the social behavior of typical individuals with Williams is their strong impulse towards social contact with strangers, although their social behavior is not always appropriate. Bellugi and colleagues have been investigating aspects of their dramatic story telling, which is peppered with ways of engaging their audience. They have found that individuals with Williams use significantly higher levels of prosody and affective language than cognitively matched children with Downs, or age matched normal controls (Losh et al, 2000, Figure below). Despite their cognitive impairments, individuals with Williams are not only sociable and affectively sensitive, they also show an abundance (or overabundance) of affectivity in both prosodic and lexical devices. Their overall pattern of hypersocial behavior is strikingly different from that shown by individuals with Down syndrome, and, in important ways, is the inverse of that seen in autism. The inner drive and excessive desire for social contact with strangers is exemplified in the words of an 8 year old child with Williams: “There are no strangers, there are only friends”.

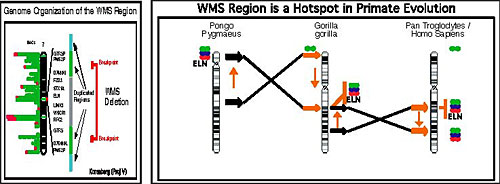

It is critical to this proposal to understand that the genetic defect that results in Williams syndrome (and that may lead to the altered social behavior!) is now known. Williams syndrome is associated with a hemizygous deletion around the elastin gene on chromosome 7, involving approximately 16 genes (Korenberg et al, 2000). More than 98% of clinically identified individuals with Williams have one copy of the elastin gene missing. Nearly all individuals with Williams also have the same breakpoints and thus the same small set of genes missing (Figure below). However, critically important to the goals of this program, a small group of Williams subjects have recently been identified who have smaller deletions of chromosome 7 including some that spare a contiguous region including three genes (CYLN2, GTF2IRD1 and GTF2I, see Korenberg, et al, 2001) that are described more fully below. While these subjects express many of the characteristics of the Williams phenotype, they appear not to demonstrate the hypersocial behavior! This proposal is thus based on the specific hypothesis that dysregulation of one or more of these three genes, either developmentally or in the mature brain, may lead to an alteration of social behavior involving hypersociability, including a strong impulse toward social contact and affective expression.

IS HYPERSOCIABILITY OBSERVED IN NONHUMAN PRIMATES?

One reason for optimism that the nonhuman primate may provide an appropriate and useful model of Williams syndrome is the recent findings of Amaral and colleagues. They have studied both adult and neonatal rhesus monkeys who were neurosurgically prepared with bilateral lesions of the amygdaloid complex (Emery et al., 2001). In the adults, the amygdala lesioned animals demonstrated a much higher level of affiliative social behavior. In many respects their behavior resembled the inappropriate “friendliness” of Williams subjects. Not only will we examine whether genes associated with Williams syndrome are preferentially expressed in the amygdala, but, by studying the brain distribution of their expression, will determine other brain regions that are potentially involved in the hypersociability and by extension, in normal social cognition. The rhesus monkey is the most appropriate animal model because of their complex social organization, use of social gestures such as facial expressions and, substantial literature on their brain organization and behavior.

| Introduction | Project 1 | Project 2 | Project 4 | Project 5 | Project 6 | Conclusion |